Новости Азербайджана

Главные новости

Xроника

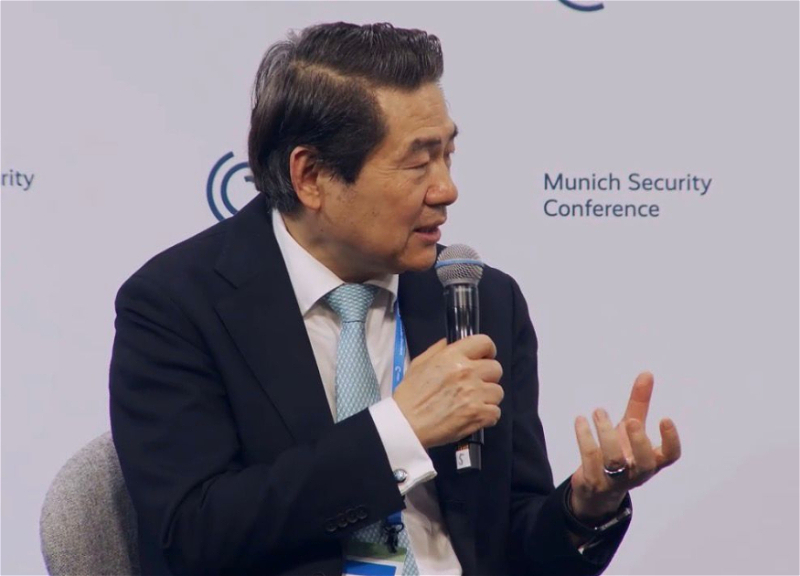

Президент Ильхам Алиев принял участие в панельных дискуссиях в Мюнхене - ФОТО - ОБНОВЛЕНО

14 февраля в рамках Мюнхенской конференции по безопасности состоялись панельные дискуссии на тему «Политика открытых коридоров? Углубление Транскаспийского сотрудничества». Как сообщает ...

Xроника

Ильхам Алиев: «Подписание официального мирного соглашения зависит от того, когда будет изменена конституция Армении» - ВИДЕО

Я надеюсь, что мы подпишем мирное соглашение в этом году. Я уже говорил об этом неоднократно, отмечая, что сам факт ...

Xроника

В Мюнхене состоялась встреча президентов Азербайджана и Украины - ОБНОВЛЕНО

14 февраля в Мюнхене состоялась встреча Президента Азербайджанской Республики Ильхама Алиева с Президентом Украины Владимиром Зеленским. Как сообщает АЗЕРТАДЖ, в ходе ...

Xроника

Президент Ильхам Алиев встретился в Мюнхене с верховным представителем ЕС по иностранным делам и политике безопасности - ОБНОВЛЕНО

14 февраля Президент Азербайджанской Республики Ильхам Алиев встретился в Мюнхене с верховным представителем Европейского Союза по иностранным делам и политике ...

Политика