Azerbaijan’s Port on China’s Road

By Katherine Schmidt

Descriptions of China’s Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) often center on China’s agency in other countries — its investments, loans, and even soft-power (e.g., cultural exchange).

However, Azerbaijan’s Baku International Sea Trade Port in Alat, a retroactively labeled “BRI” infrastructure project, is anything but centrally controlled by China. While some BRI projects are clearly led by Beijing, such as Hambantota port in Sri Lanka, other projects operate more independently.

The strategic and geographic importance of Alat Port (written as “Ələt” in Azerbaijani) pre-dates BRI. It was announced by the Azerbaijani government in 2007 — six years before President Xi Jinping’s announcement of the BRI in Kazakhstan. The port’s expansion was seen as a way for the government to diversify the economy away from dependence on oil and gas through the development of cargo and transportation services, which was a goal of the Azerbaijani government long before China introduced the concept through BRI.

Moreover, the strategic role of Azerbaijan and the Caspian Sea as connectors between the East and the West has been well-acknowledged since the times of the ancient Silk Road.

Construction of the modern port in Baku started in the mid-nineteenth century under the Russian Empire, and it officially opened in 1902. It is the largest and busiest port on the Caspian Sea and an important historical resource for trade and connectivity with surrounding countries. In recent decades, Baku has undergone rapid development (albeit often in opposition to local residents).

In January 2019, when returning to the country after just four months away, I was struck by the mounting construction and the expansion of supermarket chains such as Bravo. This development has limited the available space to expand the port’s facilities at its original location. In contrast, the surroundings of the town of Alat — a 30-minute drive down the coastline — are relatively empty and offered an attractive location for a much bigger port when construction began in 2014.

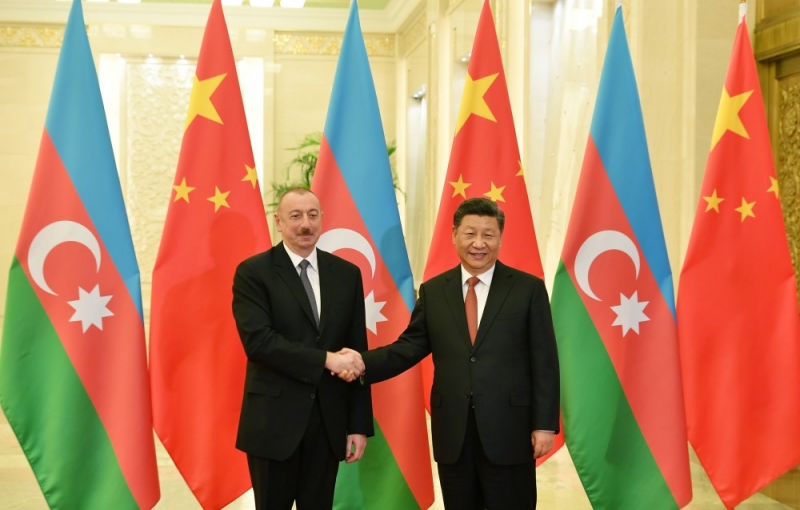

CHINA'S PRESENCE

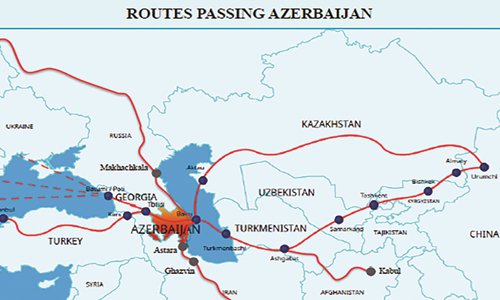

Given Azerbaijan’s support of the BRI through its memorandum of understanding and as one of the first countries to join the initiative, rhetoric surrounding the port often links it with the BRI. Additionally, the port’s strategic location is significant to one of the main proposed routes of the BRI.

The middle East-West corridor of the Economic Belt segment, the Trans-Caspian International Transport Route (“TITR”), utilizes the Caspian Sea. Potential uses of this corridor include a northern option, where goods enter from Western China into Kazakhstan through the Khorgos border crossing are shipped across the Caspian Sea from Aktau into Baku and then use the BTK railway to transfer into Turkey.

From there, goods can be shipped over the Black Sea into Greece. As such, Alat port is a key part of this segment of the Belt and Road Initiative and is often discussed in tandem with the larger TITR route.

To date, China has gifted equipment worth about $2 million and, in total, has allocated grants worth around $70 million for the New Port in Alat. Azerbaijan’s total government investment is unknown due to the lack of transparent, publicly-available state statistics, but my interviews with two experts at Port Baku indicate that the majority of funding for the estimated $544.74 million three-phase project and impetus behind the port’s creation comes from the Azerbaijani government.

One of my “Hail Marys” during my fieldwork in Baku was when I sent the Port of Baku Facebook page a message requesting an interview. I was excited to see who would answer the message—if anyone would answer. Luckily, Azerbaijani hospitality, coupled with fascination about why someone was studying the port, worked in my favor.

I met Toghrul—a U.K.-educated recent graduate working for the port—in a nearby coffee shop, where he picked me up to escort me into the office of the Port of Baku. With ample security and glimmering marble hallways proudly displaying the port’s logo, the office contained an air of formality present in many buildings used for Azerbaijani official and state-sponsored functions.

My official meeting was with Zaur Hasanov, the advisor to the Director-General at Port of Baku. He was passionate, animated, and well-spoken; during our conversation, he emphasized the construction of the new port at Alat as critical to solving the issue of limited space within the capital’s limits and as a significant victory of the Azerbaijani government.

At the time, the existing port’s size was 140 hectares. With the addition of a new free trade zone, which gained legislative approval in 2018, the size is projected to grow to 1200 hectares (approximately 1200 sports fields). This significant expansion demonstrates the substantial commitment and undertaking by the Azerbaijani government.

Mr. Hasanov firmly dismissed the idea of China leading the port’s development. To him, overseeing the construction of the port, in all of its phases, was his job, and it would be absurd to think of China managing this process. While China has certainly contributed grants and gifts to aid in the creation of the new port, there was not a perception of heavy Chinese involvement and there were no mentions of loans currently in effect during our meeting.

During another interview with Javid Akhundov, a project manager at ISR Holding Company with experience working with local shipping and logistics companies, offered an additional perspective of Chinese involvement in the port. After the obligatory round of tea, he told me that “China is far [away].”

Azerbaijan is secured by its neighbors. In contrast to countries, such as Kazakhstan, where there is both a border with China and concern over China’s involvement, Azerbaijan views potential future involvement with China as a way for both countries to benefit from the port: Azerbaijan, through diversification of its economy and increased revenue from cargo shipments, and China through its increased trade with Europe and other countries along the way. Mr. Akhundov cited China’s subsidies of COSCO, its largest shipping carrier, as one example of existing Chinese support for China-Europe routes and stated that he anticipates increased Chinese presence in the future.

Dr. Elkhan Alasgarov, head of the Baku International Policy and Security Network, added to Mr. Akhundov’s short, yet telling, description of China as “far.” He described how Azerbaijan sees China through the lens of Central Asia — meaning that China’s involvement in domestic initiatives is seen as minimal. Yet there is awareness that China is heavily involved in Kazakhstan and other countries. As such, Central Asia essentially “buffers” Azerbaijan from Chinese meddling. In Azerbaijan, China is seen less as a hostile “big brother” or threat and more as a potential partner in securing regional goals.

Given that Azerbaijan’s main source of economic wealth stems from oil, China’s investment in Alat Port, just one — albeit large — transport and infrastructure project, is relatively insignificant. Instead, Chinese influence at the port was largely reflective of China’s presence throughout the country as a whole, stretching beyond the value of investment deals. For example, during my visit to the office of Port of Baku, I was introduced to an Azerbaijani professional who was fluent in Mandarin Chinese.

In his late fifties, the man had significant experience in China and had completed his higher education there. A sense of growing Chinese-language influence was compounded by other informal conversations with a number of young researchers at the Center for Economic and Social Development who had studied Chinese and lived for a few months in Shanghai.

Additionally, the Azerbaijan University of Languages has a Confucius Institute, established in 2015 to strengthen cooperation in education between Azerbaijan and China.

Further signs of China’s presence could be seen in the billboards along the highways in Baku, which advertised Huawei smart phones. Chinese companies, Huawei and ZTE, supply the technology underpinnings the free public Wi-Fi service in Baku.

While the BRI is born from the Chinese government’s roadmap to make Beijing the center of a global network of trade that connects the East with the West, the initiative is anything but centrally maintained and controlled. In the case of Alat Port in Azerbaijan, the project is, in fact, a domestic initiative and was developed locally before receiving international attention.

Understanding these relationships and interactions between countries, such as China and Azerbaijan, will be key in understanding the impact of the BRI on changing international power dynamics.

Katherine Schmidt graduated from Georgetown University’s School of Foreign Service and conducted this research in Azerbaijan with the Center for Economic and Social Development.